Macbeth doubtless resented the inauguration of young King Duncan (Donnchad mac Crinain) in 1034 to succeed his grandfather Malcolm. Macbeth had a claim to the throne in his own right and this was strengthened by his marriage to Gruoch, herself of royal lineage.

Whatever the reason, however, Macbeth accepted Duncan as King. Perhaps his newness as Mormaer and the need to get to grips with ruling Moray softened the blow, though ambition remained.

Following a wounded King

Duncan was not a successful King and his prestige must have been dealt a severe blow when he suffered defeat during an attempted siege of Durham in 1039. This may have been the trigger for Macbeth, either acting alone or with the knowledge of other nobles, to rebel against the King who lacked the prowess and success expected of a Celtic warlord.

- Pitgaveny today, with Cameron

- Pitgaveny Spynie Palace

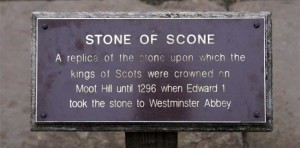

In 1040 King Duncan led a force into Moray, perhaps to bring a rebellious Macbeth to heel. In August 1040 Macbeth defeated and killed Duncan at Pitgaveny near Elgin then moved quickly to Scone where he was inaugurated King in the traditional way at the Moot Hill.

- Stone of Scone Sign

- Stone of Scone

Duncan’s sons Malcolm and Donald Ban were driven into exile. A King’s death at the hands of his own people in this way was not unusual in Celtic society. This was no murder, whatever Shakespeare would have us believe.